What Do You Wish The American People Better Understood About Military Service Or Military Families?

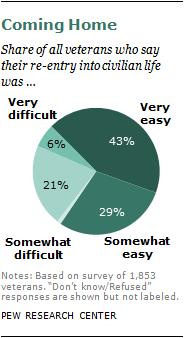

Armed forces service is hard, enervating and unsafe. But returning to civilian life also poses challenges for the men and women who accept served in the military machine, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey of ane,853 veterans. While more than vii-in-ten veterans (72%) report they had an easy time readjusting to civilian life, 27% say re-entry was difficult for them—a proportion that swells to 44% among veterans who served in the x years since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Armed forces service is hard, enervating and unsafe. But returning to civilian life also poses challenges for the men and women who accept served in the military machine, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey of ane,853 veterans. While more than vii-in-ten veterans (72%) report they had an easy time readjusting to civilian life, 27% say re-entry was difficult for them—a proportion that swells to 44% among veterans who served in the x years since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

Why do some veterans have a difficult fourth dimension readjusting to noncombatant life while others brand the transition with little or no difficulty? To respond that question, Pew researchers analyzed the attitudes, experiences and demographic characteristic of veterans to identify the factors that independently predict whether a service fellow member will take an piece of cake or difficult re-entry experience.

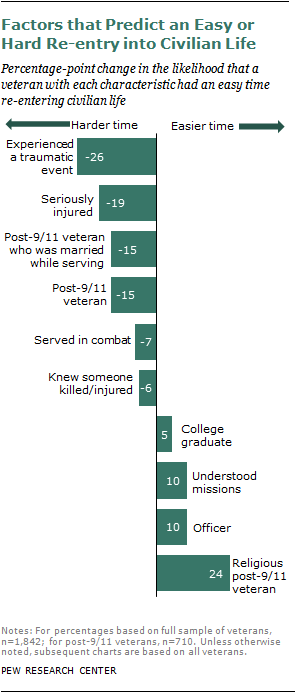

Using a statistical technique known as logistic regression, the analysis examined the impact on re-entry of 18 demographic and attitudinal variables. Iv variables were establish to significantly increase the likelihood that a veteran would take an easier fourth dimension readjusting to civilian life and six factors predicted a more than difficult re-entry experience.

According to the study, veterans who were commissioned officers and those who had graduated from college are more likely to have an easy time readjusting to their post-military machine life than enlisted personnel and those who are high school graduates.1 Veterans who say they had a clear understanding of their missions while serving likewise experienced fewer difficulties transitioning into civilian life than those who did not fully sympathize their duties or assignments.

In contrast, veterans who say they had an emotionally traumatic feel while serving or had suffered a serious service-related injury were significantly more likely to report issues with re-entry, when other factors are held constant.

In contrast, veterans who say they had an emotionally traumatic feel while serving or had suffered a serious service-related injury were significantly more likely to report issues with re-entry, when other factors are held constant.

The lingering consequences of a psychological trauma are particularly striking: The probabilities of an piece of cake re-entry drop from 82% for those who did not experience a traumatic event to 56% for those who did, a 26 percent betoken decline and the largest change—positive or negative—recorded in this written report.2

In add-on, those who served in a combat zone and those who knew someone who was killed or injured also faced steeper odds of an easy re-entry. Veterans who served in the mail service-nine/eleven menstruum also report more difficulties returning to civilian life than those who served in Vietnam or the Korean War/Earth State of war Two era, or in periods between major conflicts.

Two other factors significantly shaped the re-entry experiences of post-9/xi veterans but appear to have had fiddling impact on those who served in previous eras. Post-9/11 veterans who were married while they served had a significantly more hard time readjusting than did married veterans of past eras or single people regardless of when they served.

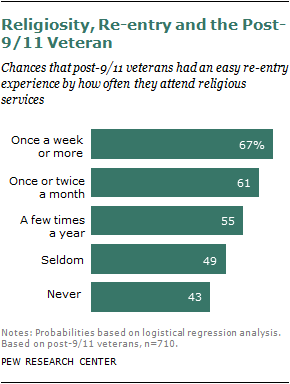

At the same time, higher levels of religious belief, equally measured by frequent attendance at religious services, dramatically increases the odds that a post-9/eleven veteran will have an easier fourth dimension readjusting to noncombatant life. According to the assay, a recent veteran who attends religious services at least once a week has a 67 percentage chance of having an like shooting fish in a barrel re-entry experience. Among post-nine/eleven veterans who never attend services, the probability drops to 43%.3 Among veterans of other eras, current omnipresence at religious services is not correlated with ease of re-entry.4

Eight other variables tested in the model proved to exist poor predictors of how easily a veteran made the transition from armed forces to civilian life. They are race and ethnicity (separate variables tested the event of being white, black, Hispanic or another race); historic period at time of discharge; whether the veteran had children younger than 18 while serving; how long the veteran was in the military machine; and how many times the veteran had been deployed.

Predicting the Ease of Re-entry

This analysis employs a statistical technique known equally logistic regression to measure the effect of whatever given variable on the likelihood that a veteran had an easy or hard time re-entering civilian life while controlling for the effects of all other variables.

To identify the factors that best predicted an easy re-entry, xviii contained variables were included in the regression model. The variables were chosen based on their predictive ability in previous research. The demographics were: veteran's age at discharge; how long the individual served; the veteran's education, race and ethnicity (tested as iv separate variables: white, blackness, Hispanic or another race); whether the veteran was married or had young children while in the service; highest rank attained; and era in which the veteran served. Other variables tested the bear upon of specific experiences on re-entry: whether the veteran had been seriously injured while serving; experienced a traumatic or emotionally distressing event; served in a combat or state of war zone; or served with someone who had been killed or injured. A question that asked veterans whether they understood about or all of the missions in which they participated besides was included.

Of the eighteen variables in the model, ten turn out to exist significant predictors of a veteran's re-entry feel. Four were positively associated with re-entry: beingness an officer; having a consistently clear understanding of the missions while in the service; being a college graduate; and, for post-9/eleven veterans simply not for those of other eras, attending religious services often. Six variables were associated with a diminished probability that a veteran had an piece of cake re-entry. They were: having a traumatic experience; beingness seriously injured; serving in the post-ix/11 era; serving in a combat zone; serving with someone who was killed or injured; and, for mail service-9/eleven veterans but not for those of other eras, beingness married while in the service.

Factors that Make Readjustment Harder

Overall, the survey establish that a plurality of all veterans (43%) say they had a "very easy" time readjusting to their post-military lives, and 29% say re-entry was "somewhat easy." Only an additional 21% say they had a "somewhat difficult" time, and 6% had major problems integrating back into civilian life.

Amidst the 18 variables tested, veterans who experienced emotional or physical trauma while serving are at the greatest chance of having difficulties readjusting to civilian life. According to the analysis, having an emotionally distressing experience reduces the chances that a veteran would have a relatively easy re-entry by 26 percentage points compared with a veteran who did not take an emotionally distressing experience. Similarly, suffering a serious injury while serving reduces the probability of an like shooting fish in a barrel re-entry by 19 per centum points, from 77% to 58%.

Amidst the 18 variables tested, veterans who experienced emotional or physical trauma while serving are at the greatest chance of having difficulties readjusting to civilian life. According to the analysis, having an emotionally distressing experience reduces the chances that a veteran would have a relatively easy re-entry by 26 percentage points compared with a veteran who did not take an emotionally distressing experience. Similarly, suffering a serious injury while serving reduces the probability of an like shooting fish in a barrel re-entry by 19 per centum points, from 77% to 58%.

Overall, the survey found that serious injuries and exposure to emotionally traumatic events are relatively common in the military. Most a third (32%) of all veterans say they had a military-related experience while serving that they plant to be "emotionally traumatic or distressing"—a proportion that increases to 43% amid those who served since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Well-nigh one-in-x veterans (10%) suffered a serious injury; of those who served in the mail service-9/11 era, 16% suffered a serious injury, in part considering service members with serious injuries are more than likely to survive today than in previous wars, when those with serious injuries died.

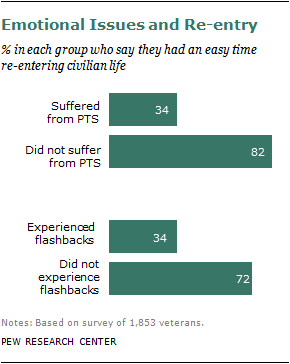

The survey also pinpoints some of the specific problems faced by returning service members who suffered service-related emotional trauma or serious injury. More than half (56%) of all veterans who experienced a traumatic event say they have had flashbacks or repeated distressing memories of the experience, and nearly half (46%) say they take suffered from postal service-traumatic stress.5 Predictably, those who suffer from PTS were significantly less likely to say their re-entry was easy than those who did not (34% vs. 82%).

According to the model, serving in a gainsay zone reduces the chances that a veteran will have an easier time readjusting to civilian life (78% for those who did non serve in a combat zone to slightly more than 71% for those who did). Knowing someone who was killed or injured also lessens the probability that a veteran volition take an easy re-entry past six percentage points (73% vs. 79%).

Service Era and Re-entry

Many veterans who served after Sept. 11, 2001, take experienced difficulties readjusting to noncombatant life. The model predicts that a veteran who served in the post-9/11 era is fifteen percentage points less likely than veterans of other eras to have an easy time readjusting to life after the military (62% vs. 77%).

A word of caution about comparing re-entry experiences between service eras. Those in the post-9/11 era were interviewed relatively before long after they left the military, and their views could reflect the immediacy of their experience and could alter over time. For earlier generations of veterans, their views could accept changed from what their views were at a like point in their postal service-military lives.

Likewise, the overall view of veterans of earlier eras could change equally members of this generation die and the composition of the cohort becomes dissimilar. As a consequence, these results are best interpreted every bit the views and experiences of current living veterans from each era, and not necessarily the views each generation held in the years immediately after leaving the service.

Matrimony and Re-entry

The analysis produced a surprise. Post-9/xi veterans who were married while they were in the service likewise had a more difficult time readjusting to life later the military. Overall, being married while serving reduces the chances of an easy re-entry from 63% to 48%.

At first glance, this finding seems counterintuitive. Shouldn't a spouse be a source of comfort and support for a discharged veteran? Other studies of the general population have shown that marriage is associated with a number of benefits, including better health and higher overall satisfaction with life.half dozen

At first glance, this finding seems counterintuitive. Shouldn't a spouse be a source of comfort and support for a discharged veteran? Other studies of the general population have shown that marriage is associated with a number of benefits, including better health and higher overall satisfaction with life.half dozen

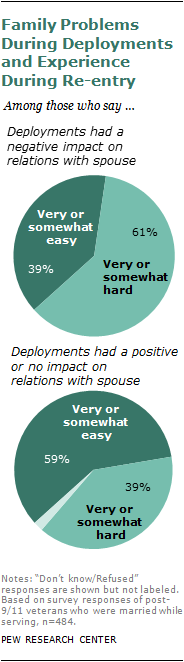

In fact, the answer to another survey question points to a likely explanation. Mail service-9/xi veterans who were married while in the service were asked what impact deployments had on their relationship with their spouse. Nearly half (48%) say the affect was negative, and this group is significantly more likely than other veterans to accept had family problems subsequently they were discharged (77% vs. 34%) and to say they had a hard re-entry.

Amongst those married while they were in the service, about six-in-10 (61%) postal service-ix/11 veterans who had experienced marital problems while deployed also had a difficult re-entry. In contrast, nigh 4-in-x veterans (39%) who reported that deployments had a positive or no touch on on their spousal relationship say they had problems re-entering civilian life—nigh identical to the proportion of then-single postal service-nine/eleven veterans (37%) who experienced difficulties re-entering noncombatant life.

Taken together, these findings underscore the strain that deployments put on a union before a married veteran is discharged and after the veteran leaves the service to rejoin his or her family.

Factors that Improve the Chances of an Easy Re-entry

Iii variables tested in the model—rank at the time of discharge, how well the mission was understood and education level—emerged as statistically meaning predictors of an piece of cake re-entry experience for all veterans. A fourth variable, religiosity as measured by service attendance, is a powerful predictor of an easier re-entry experience for post-9/11 veterans simply not for those who served in earlier eras.

The model predicts that commissioned officers are ten percentage points more likely than enlisted personnel to experience few if whatsoever difficulties readjusting to life at dwelling (85% vs. 74%),7 when all other factors are held constant. Veterans who say they conspicuously understood their missions while serving also were more likely than those who did not to take an easier re-entry (77% vs. 67%).eight

College-educated veterans also are predicted to have a somewhat easier fourth dimension readjusting to life afterward the military than those with only a high school diploma. Co-ordinate to the analysis, a veteran with a college caste is v pct points more than likely than a loftier school graduate to have an like shooting fish in a barrel fourth dimension with re-entry (78% vs. 73%).

Again, a word of caution is in order. Veterans in the survey were asked how many years of schoolhouse they take attended. Some of these college graduates may have earned their degree well after their belch from the service.

Religiosity and Re-entry

Among the larger factors influencing the re-entry experience of post-ix/11 veterans is religious faith, as measured by how frequently a recent veteran attends religious services. Recent veterans who attend services at least once a calendar week are 24 percentage points more probable to say they had an easy re-entry dorsum into civilian life than those who never attend services (67% vs. 43%). This finding is consequent with other studies of the general population that suggest religious belief is correlated with a number of positive outcomes, including amend physical and emotional health, and happier and more satisfying personal relationships.9

The impact of religious observance vanishes if the sample is based only on those who completed their service before Sept. xi, 2001. In fact, there is barely a one percentage indicate departure in the probability of an easy re-entry between older veterans who currently attend religious services and those who never do.

The impact of religious observance vanishes if the sample is based only on those who completed their service before Sept. xi, 2001. In fact, there is barely a one percentage indicate departure in the probability of an easy re-entry between older veterans who currently attend religious services and those who never do.

As noted earlier, one reason for the absence of an impact may exist related to the question measuring electric current attendance at religious services. This measure of attendance may exist a skilful proxy for the religious convictions of more recent veterans. Just information technology may be a poor estimate of how religious older veterans were immediately later on they were discharged from the service. Over the years the religious belief of these older veterans may have inverse, obscuring the bear upon of religious confidence on their re-entry feel.

What Do You Wish The American People Better Understood About Military Service Or Military Families?,

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2011/12/08/the-difficult-transition-from-military-to-civilian-life/

Posted by: brinkthapide.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Do You Wish The American People Better Understood About Military Service Or Military Families?"

Post a Comment